Microsoft claims that "the new Windows is available on the widest array of devices," but the Internet had a minor panic attack when requirements were outlined yesterday.

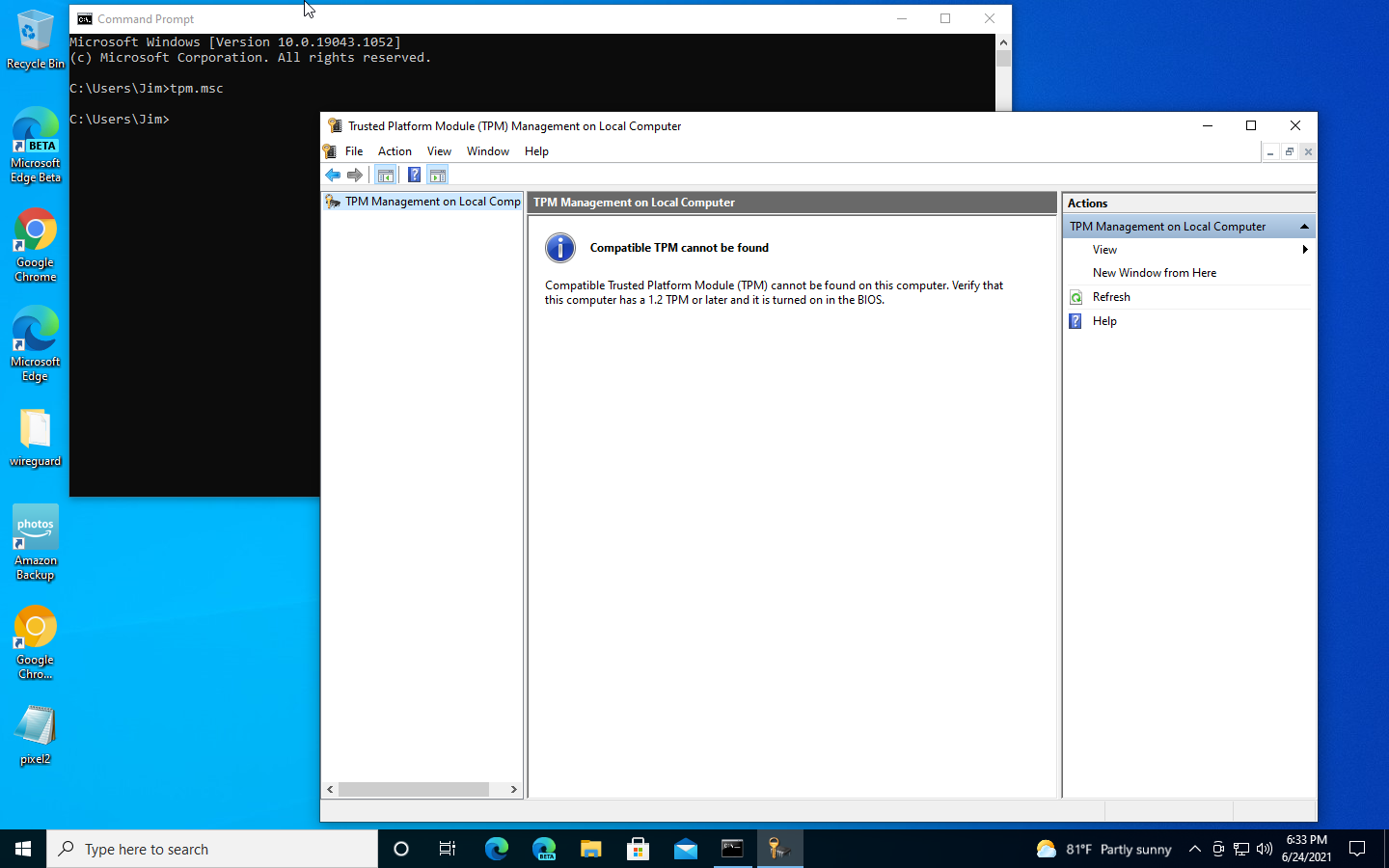

Microsoft claims that "the new Windows is available on the widest array of devices," but the Internet had a minor panic attack when requirements were outlined yesterday. Our daily-driver Windows 10 VM didn't have TPM support, as shown in this screenshot of tpm.msc. So we'll walk you through how to get TPM support—on hardware machines as well as in VMs.Jim Salter

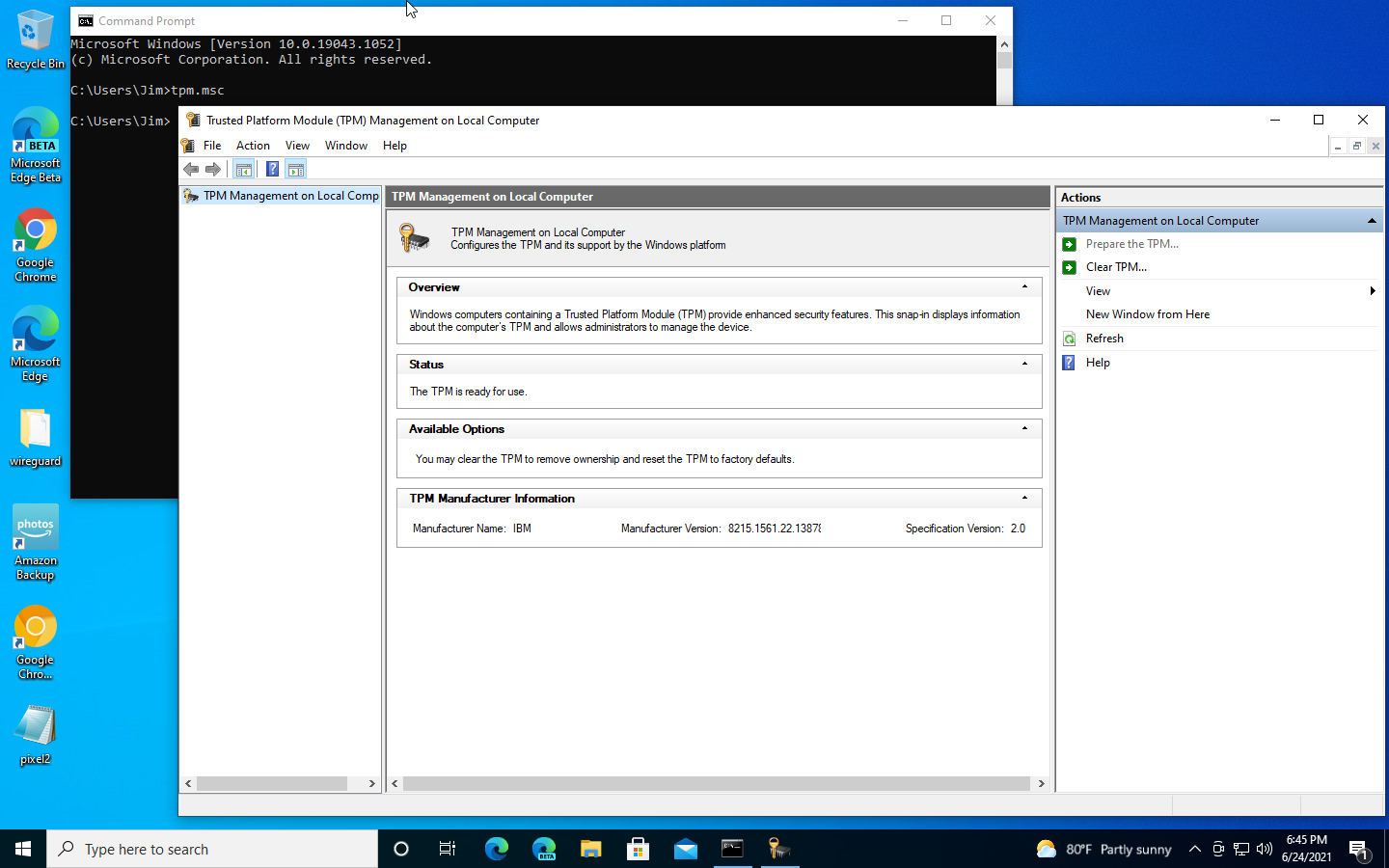

Our daily-driver Windows 10 VM didn't have TPM support, as shown in this screenshot of tpm.msc. So we'll walk you through how to get TPM support—on hardware machines as well as in VMs.Jim Salter

Since Microsoft's announcement of Windows 11 yesterday, one concern has reverberated around the web—what's this about a Trusted Platform Module requirement?

Windows 11 is the first Windows version to require a TPM, and most self-built PCs (and cheaper, home-targeted OEM PCs) don't have a TPM module on board. Although this requirement is a bit of a mess, it's not as onerous as millions of people have assumed. We'll walk you through all of Windows 11's announced requirements, including TPM—and make sure to note when all this is likely to be a problem.

General hardware requirements

Although Windows 11 does bump general hardware requirements up some from Windows 10's extremely lenient minimums, it will still be challenging to find a PC that doesn't meet most of these specifications. Here's the list:

- CPU—1 GHz or faster, two or more cores, x86_64 or ARM64 only

- RAM—4GiB or more

- Storage—64GB minimum for installation... but we'd recommend at least 128GB for a vaguely normal system

- Graphics—Compatible with DX12 or later, with WDDM 2.0 driver

- Firmware—UEFI, Secure Boot capable

- TPM—Trusted Platform Module 2.0 is listed as a minimum requirement; TPM 1.2 may or may not be "good enough"—but read on before throwing your hands up in despair!

- Display—720p minimum resolution, nine-inch minimum diagonal measurement, 8 bits per color channel or higher

In addition to those hardware requirements, Windows 11 Home requires Internet connectivity and a Microsoft cloud account. The Microsoft account and Internet connectivity are only mandatory for Home—not Pro. No word yet on whether there will be a workaround, like the current "don't plug the network cable in until after setup" dance.

The CPU requirement may be more or less of a problem than it initially seems. Microsoft has a relatively short list of supported CPUs from three major manufacturers (AMD, Intel, and Qualcomm) that generally goes back to Ryzen 2500 or Intel 8th generation Core—no farther. We're not certain how trustworthy that list is, though. We strongly suspect Windows 11 will work fine on many considerably older processors.

If Microsoft codes a hardware requirement checklist into the installer or boot sequence, many CPUs that would have otherwise worked well will be unusable. This seems fairly unlikely, but (pardon the well-worn expression) only time will tell for certain.

A closer look at the Trusted Platform Module requirement

Most build-your-own-PC motherboards, even flagship boards, don't come with a hardware TPM module installed. However, most of those boards do theoretically support hardware TPM, with a special 19-pin header ready to plug one in. Honestly, it's a very niche, specialty device that few users have ever purchased.

At least, very few people bought optional hardware TPM until yesterday, after seeing the Windows 11 requirements and subsequently panicking. Within hours of Microsoft Chief Product Officer Panos Panay's Windows 11 introduction, the entire stockpile of most manufacturers' readily available TPM modules were sold out by Windows 10 users trying to make certain they could run 11.

If you didn't get one of the few TPM modules available yesterday, don't worry—you almost certainly don't need one. OEM hardware TPM is generally considered the most hardened version, and it's soldered directly to the board in PCs intended for enterprise use. Less-hardened firmware TPM support is built right into modern AMD and Intel processors, and that will satisfy Windows 11's TPM requirement just fine.

It's a bit difficult to get a complete, accurate list of all CPUs with support for onboard, firmware-based TPM, largely because the demand for it was fairly low until this week. As far as we can see, every x86_64 CPU on Microsoft's supported processor lists includes that support.

Intel calls its firmware-based TPM iPPT (Intel Platform Protection Technology), and AMD calls its own fTPM (Firmware Trusted Platform Module). Generally speaking, iPPT shows up in most Haswell (4th-gen Core) CPUs, although the K-series gaming models inexplicably fail to get iPPT until Skylake (6th-gen Core). On the AMD side, we see fTPM show up with Ryzen 2500 and up.

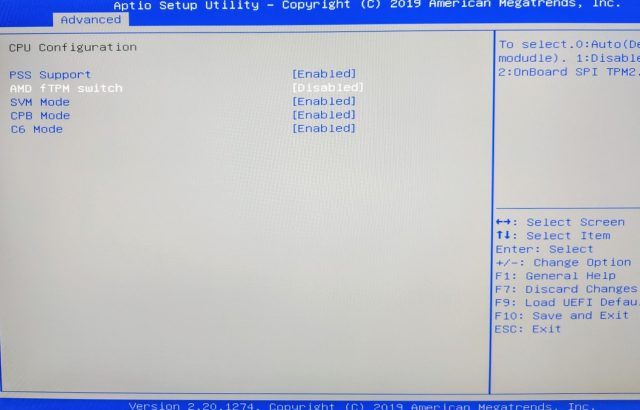

There is one more gotcha to navigate, though. Although the vast majority of semi-modern CPUs support firmware TPM, almost all motherboards ship with it disabled in BIOS. So you'll need a three-finger salute and a deep dive through the "advanced" part of your machine's BIOS to try to find and enable that support if you need it.

OEM motherboards are just as likely to have fTPM disabled by default—and unfortunately, they frequently don't expose the setting to enable it, even when the CPU otherwise supports it. If you have a pre-built system from Dell or HP that didn't include a hardware TPM, you could be stuck with no way forward.

To determine whether TPM support is available and working under Windows, run the command tpm.msc. This will spawn a TPM dialog that shows whether you have TPM support and what version (1.2 or 2.0) it is. (You can also interact with the TPM by clearing or "preparing" it, but that's not something you need to do—or should do—unless specifically asked. Messing with your TPM can permanently brick Bitlocker volumes, and it might even deactivate Windows in some cases.)

Let’s talk about UEFI and Secure Boot

Microsoft lists Universal Extensible Firmware Interface (UEFI) support and Secure Boot capability as hard requirements for Windows 11. Much like with the CPU requirements, we're currently hesitant to take these requirements at face value.

The requirement for UEFI seems likely to be just what it says on the tin—no more legacy BIOS installs for anyone!—but there might be a slight odor of weasel in the phrasing "Secure Boot capability." We won't know for sure until Windows 11 Insider images start becoming available, but we suspect that "capability" is likely an important word. Secure Boot itself may not be mandatory.

If you're rocking a pre-built OEM PC, these requirements are not likely to affect you. Any system with both CPU and TPM support modern enough to run 11 will have UEFI firmware, and its current Windows 10 installation will be running on it.

But if you built your own PC, you may have an annoying problem. Most enthusiast boards allow booting from either BIOS or UEFI, and if you installed Windows under BIOS, you won't be able to simply convert it to UEFI. With enough determination and technical ability, it's possible to Frankenstein a BIOS installation of Windows into new life under UEFI, but it's simply not going to be worth it for most Windows users, who will need to do a clean reinstall.

The problem becomes even more significant for those running virtual machines. Several virtualization platforms (including Linux KVM) default to BIOS rather than UEFI boot for guests. It's simpler, it generally boots quicker, and it has been around a lot longer. Why fix what's not broken? If your daily driver Windows 10 VM is booting from BIOS, you'll be stuck with the same can't-get-there-from-here issues that PC builders who selected a BIOS boot had.

Windows, UEFI, TPM, and the Linux Kernel Virtual Machine

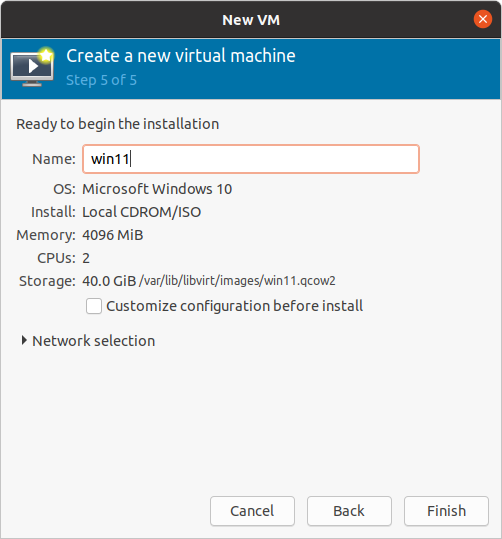

KVM guests almost always default to BIOS boot—to choose UEFI, you'll need to tick "Customize configuration before install." If you miss this step now, you won't be able to get back to it later!Jim Salter

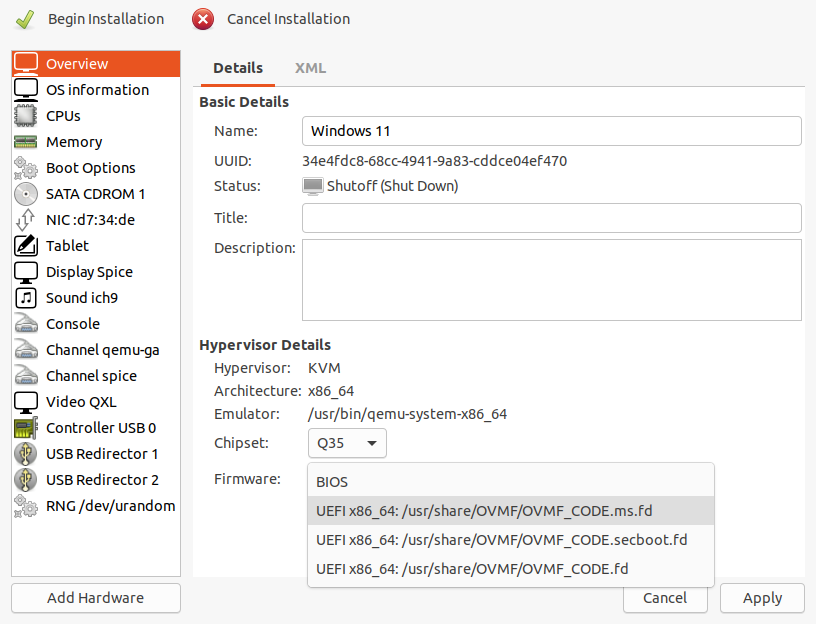

KVM guests almost always default to BIOS boot—to choose UEFI, you'll need to tick "Customize configuration before install." If you miss this step now, you won't be able to get back to it later!Jim Salter In the Overview section, change the firmware from its default of BIOS to OVMF_CODE.fd or to OVMF_CODE.secboot.fd. OVMF_CODE.ms.fd did not work in our testing!Jim Salter

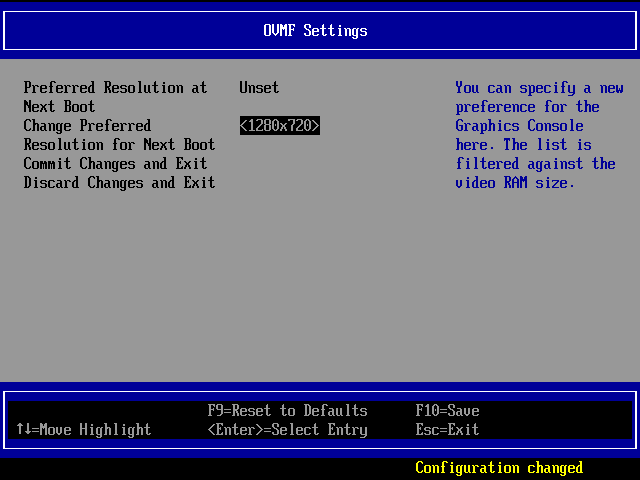

In the Overview section, change the firmware from its default of BIOS to OVMF_CODE.fd or to OVMF_CODE.secboot.fd. OVMF_CODE.ms.fd did not work in our testing!Jim Salter OVMF unfortunately defaults the hardware display size to 640x480, and Windows won't allow you to change it... instead, you'll need to press ESC during the UEFI boot and fix the "hardware" display size here. We needed two guest reboots before our shift to 1280x720 took effect in Windows.Jim Salter

OVMF unfortunately defaults the hardware display size to 640x480, and Windows won't allow you to change it... instead, you'll need to press ESC during the UEFI boot and fix the "hardware" display size here. We needed two guest reboots before our shift to 1280x720 took effect in Windows.Jim Salter

We use Linux KVM and the virt-manager management tool extensively, and our VMs have almost all been BIOS-based until this point. Getting a Windows 10 guest running with what should be everything it needs to update to 11 was a bit of a challenge, so we'll walk you through the basics right now.

First of all, new guests created by virt-manager are BIOS-based by default—and they can't be changed once created. When making any new VM intended to run Windows 11, you must check the Customize configuration before install box on the "Finish" dialog. Checking this box allows you to visit the guest hardware configs before initializing the new VM. And that's a must since the firmware becomes immutable once the guest is initialized.

Under the "Overview" section, the bottom drop-down menu for firmware defaults to BIOS, but it has three UEFI options available beneath it. In our testing, OVMF_CODE.fd and OVMF_CODE.secboot.fd both work, but OVMF_CODE.ms.fd does not, or at least not with Windows 10. When we tried using OVMF_CODE.ms.fd firmware, Windows 10 installed fine, but it believed the signatures for our VirtIO drivers were invalid, so it refused to load them on the first actual boot.

Blowing away that VM and trying again with OVMF_CODE.fd UEFI firmware worked fine, even without reinstalling Windows 10. Simply creating a new VM with the appropriate firmware while pointing its virtual disk to the already-installed Windows 10 UEFI image worked like a charm.

The next papercut we suffered was due to display resolution—booting a KVM guest from UEFI fixes the display resolution to a single setting, which Windows will then refuse to alter. To fix the issue, you'll need to press esc during the UEFI boot sequence. You can set your preferred display resolution under OVMF Settings. It's at 640x480 by default, and we changed ours to 1280x720 (aka 720p). Our change didn't take effect on this boot—we needed to reboot the guest once again before Windows noticed the change.

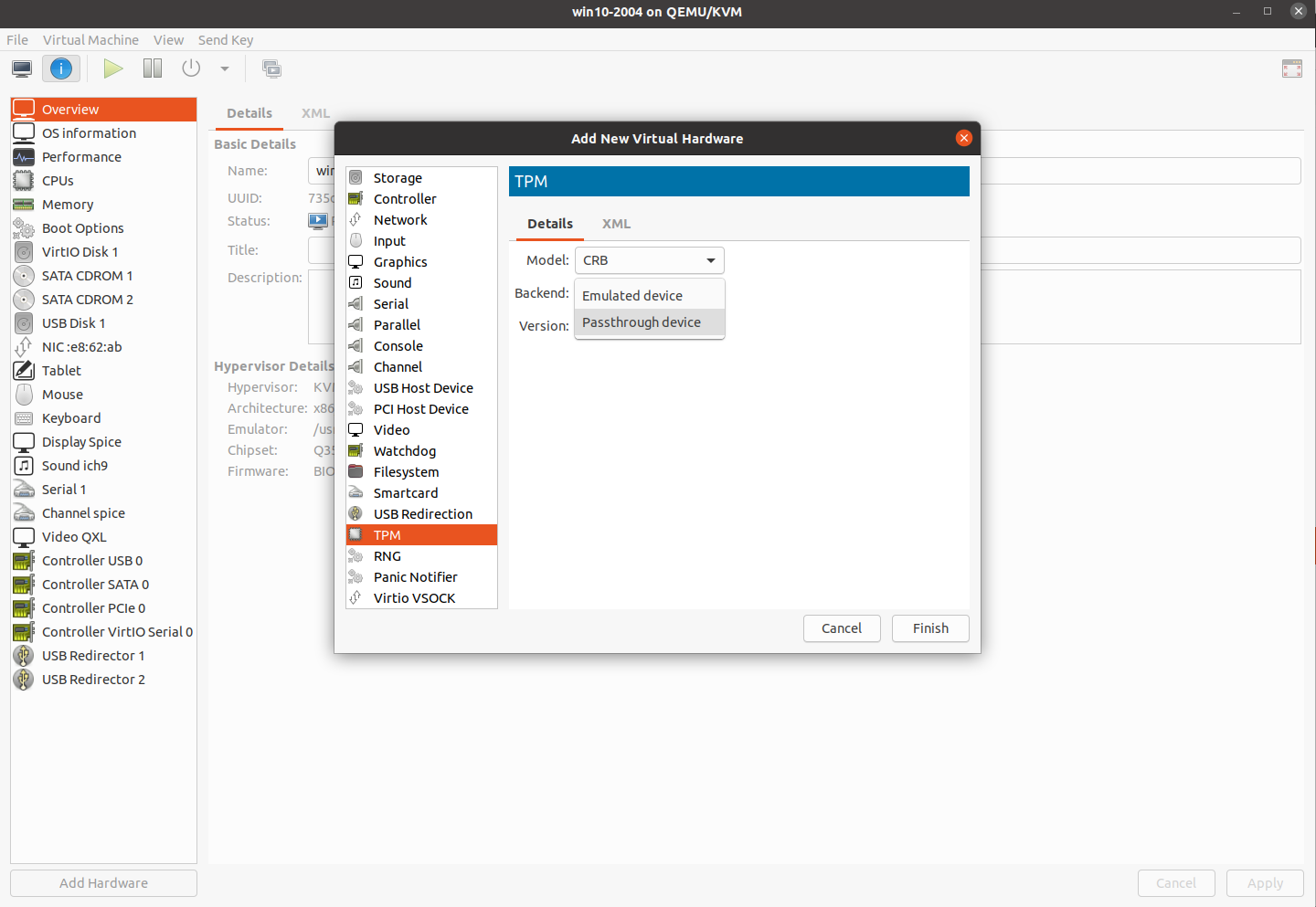

After all that work, only TPM support is left—and that's considerably simpler to address. TPM hardware can be added to an existing VM at any time by clicking "Add Hardware" and selecting "TPM" from the list of hardware types. You have three choices here: model, backend, and version.

Passthrough TPM

Adding a TPM to your KVM guest can be done at any time—unlike selecting UEFI firmware, it doesn't need to be done prior to the guest's first initialization.Jim Salter

Adding a TPM to your KVM guest can be done at any time—unlike selecting UEFI firmware, it doesn't need to be done prior to the guest's first initialization.Jim Salter Ubuntu 20.04's AppArmor profile for libvirt is too restrictive—it doesn't allow access to /dev/tpm0. We'll show you how to fix that below.Jim Salter

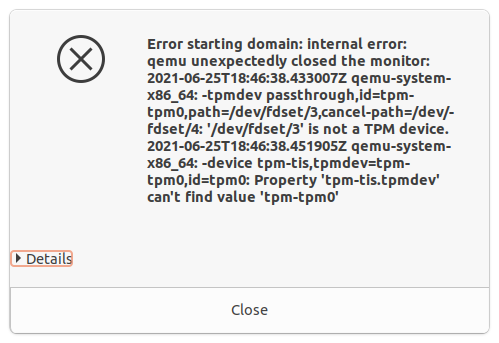

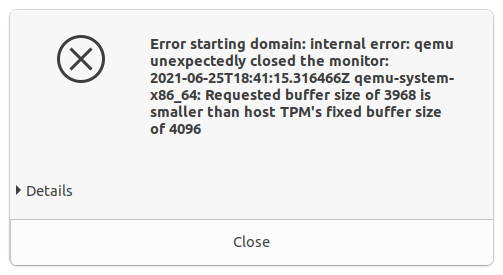

Ubuntu 20.04's AppArmor profile for libvirt is too restrictive—it doesn't allow access to /dev/tpm0. We'll show you how to fix that below.Jim Salter If you picked the wrong TPM model when adding a TPM passthrough, you'll get an error like this one when attempting to boot the guest. Just switch to the other one (CRB to TIS or TIS to CRB) and you'll be good to go.Jim Salter

If you picked the wrong TPM model when adding a TPM passthrough, you'll get an error like this one when attempting to boot the guest. Just switch to the other one (CRB to TIS or TIS to CRB) and you'll be good to go.Jim Salter

If your host system has TPM available (and enabled, if it's fTPM as described above), you can use "Passthrough device" as the backend. This changes the third choice from "version" to "device path," which will default to tpm0. The Model is still an important choice, though, as it will need to match your system's hardware TPM. On a Ryzen 7 3700X system we tested, TIS worked, but the default CBR model failed with an error about fixed buffer length mismatches.

Ubuntu users will have another step to take here—AppArmor will break the VM's attempts to access the passed-through TPM, so it will need to be nerfed. Edit the file /etc/apparmor.d/abstractions/qemu and find the section that enables access to /dev/net/tun—immediately above that line, add a new line /dev/tpm0 rw, so that the section now looks like this:

signal (receive) peer=libvirtd,

signal (receive) peer=/usr/sbin/libvirtd,

/dev/tpm0 rw,

/dev/net/tun rw,

/dev/kvm rw,

/dev/ptmx rw,

@{PROC}/*/status r,

Save the file, then reinitialize AppArmor with systemctl restart apparmor and you're off to the races. TPM passthrough will now work fine in your virtual machines without needing to disable AppArmor's significant security barrier along the way.

Emulated TPM

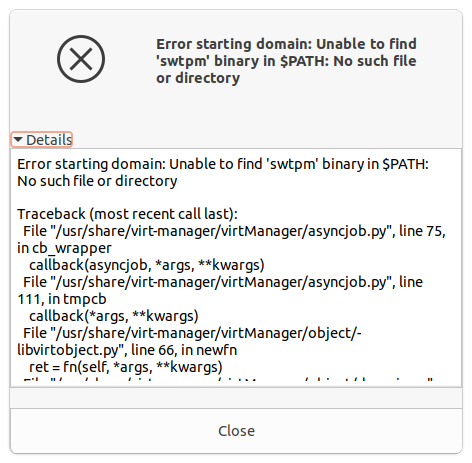

If you haven't actually installed a software TPM on your Ubuntu 20.04 system, you'll need to do so first—otherwise, you get this nasty "binary not found" error in virt-manager.Jim Salter

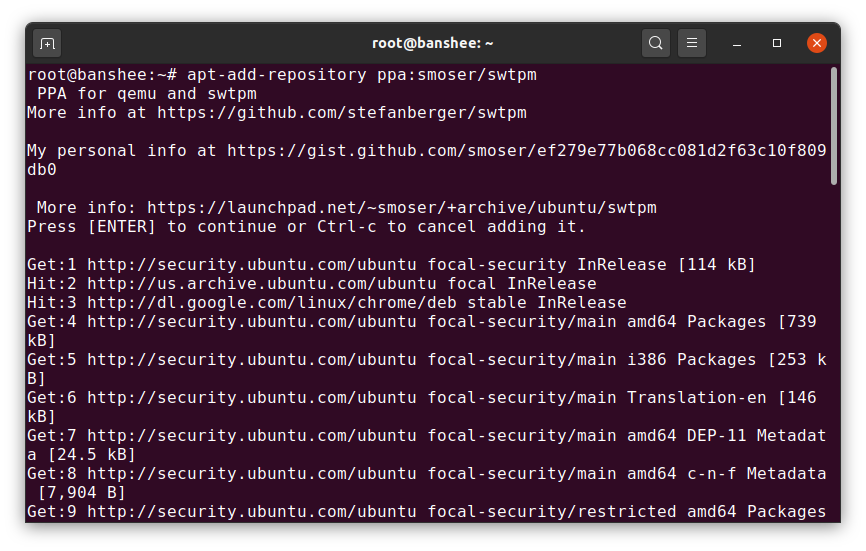

If you haven't actually installed a software TPM on your Ubuntu 20.04 system, you'll need to do so first—otherwise, you get this nasty "binary not found" error in virt-manager.Jim Salter As of this moment, there's no swtpm in Canonical repos—and the one in the Snap store doesn't seem to work with virt-manager. So you'll need to add smoser's PPA as shown here.Jim Salter

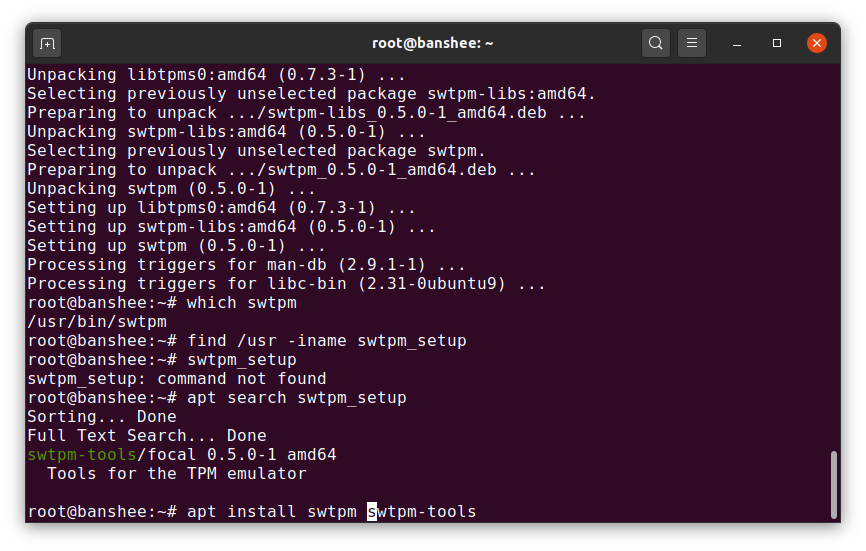

As of this moment, there's no swtpm in Canonical repos—and the one in the Snap store doesn't seem to work with virt-manager. So you'll need to add smoser's PPA as shown here.Jim Salter With smoser's swtpm repo installed, you're ready to apt install—be sure to install both swtpm and swtpm-tools, as shown. Virt-manager needs them both.Jim Salter

With smoser's swtpm repo installed, you're ready to apt install—be sure to install both swtpm and swtpm-tools, as shown. Virt-manager needs them both.Jim Salter With swtpm and swtpm-tools installed on the host and an emulated CBR 2.0 TPM installed in the guest hardware, Windows 10's tpm.msc reports full TPM capabilities!Jim Salter

With swtpm and swtpm-tools installed on the host and an emulated CBR 2.0 TPM installed in the guest hardware, Windows 10's tpm.msc reports full TPM capabilities!Jim Salter

If you don't have or don't want to use hardware or firmware TPM support on your VM's host device, you can install an emulator instead. We used the swtpm project, which required an extra repository to be added to our Ubuntu 20.04 system:

root@banshee:~# apt-add-repository ppa:smoser/swtpm

root@banshee:~# apt install swtpm swtpm-toolsWe've omitted a mountain of diagnostic info that scrolls by in each of these steps, but they do the trick. Take note that we needed swtpm-toolsin addition to swtpm itself.

Once the proper packages have been added, you can select Emulated device as your TPM Backend in virt-manager, and you're set. When in emulated mode, we had no trouble out of Windows 10 with either CBR or TIS model TPM, all of which detected just fine as fully supported TPM 2.0 devices under tpm.msc in our UEFI Windows 10 guest.

Finally, note that passing through a hardware TPM required updating libvirtd's AppArmor profile, but running an emulated one does not. Access to swtpm works fine with the stock AppArmor profile.

Listing image by Microsoft

"here" - Google News

June 26, 2021 at 03:05AM

https://ift.tt/3zWcLBU

Here’s what you’ll need to upgrade to Windows 11 - Ars Technica

"here" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2z7PfXP

https://ift.tt/2Yv8ZPx

No comments:

Post a Comment